When studying 16th and 17th century obstetrics texts from Europe, it is hard to miss the name Jacques Guillemeau. His unique attributes – in personality or otherwise – propelled him to a status of success that very few other surgeons of the time had seen. Being not only the son of the royal surgeon but also the nephew of a surgeon made his path in life clear from his adolescence. Starting with an apprenticeship at a young age, then moving to “Montpellier – a city renowned for the study of medicine” gave him a great foundation to his future enabling to achieve much in his lifetime (Long, 246). His education peaked when he became a student to the renowned Ambroise Paré – a man known for his innovations in surgery, his work in obstetrics, and being the personal surgeon to four French kings. Paré had a great influence on Guillemeau’s education as well as his focus on obstetrics. In their work together, Paré and Guillemeau concentrated on one major topic regarding the female anatomy – clitoroplasty or better known as vaginal “vaginal rejuvenation.” First Paré and then Guillemeau wrote about the procedures on how to repair vaginal lacerations that occurred during childbirth.

Jacques Guillemeau connection with women of early modern Europe is mainly through obstetrics. Just as he was influential in other medical areas, he also made an impact on the studies of women’s reproductive system and childbirth. However, he also played a major role in devaluing the position of midwives during childbirth. Guillemeau was instrumental in the transition that took place between midwives controlling every aspect of childbirth to the need of the presence of a physician or a surgeon. He made his opinions a public matter through his writings. His efforts were based on the conviction that female midwives did not receive formal education and thus were simply incompetent to have the know-how on safe childbirth. Later, he would readjust some of his writings to say that he felt that while midwives’ traditional roles were important in building relationships with the mother and child-birthing situations, however, there was a clear line between their roles and the roles of an educated physician.

Regardless of his disservice to women of the time, Guillemeau continued to grow. His “connections to Paré, as well as a host of other physicians and surgeons, led to his promotion to the grade of ordinary surgeon to King Henri III” (Long, 247). Being fluent in Latin gave him the capability to translate Paré’s works from French to Latin, so that the texts were accessible for not only surgeons but also physicians. In a weird twist of irony, Guillemeau’s legitimacy was questioned as well. The medical faculty of Paris questioned his capability of translating the documents accurately as he was only a surgeon. The speculation didn’t stop them from publishing the material and in fact, they even attributed to translation to him. This not only established him as a successful surgeon and a published writer, it also elevated the status of all surgeons. Thus, Jacques Guillemeau holds a unique position in early modern European medicine as he was possibly the only man who managed to become a successful surgeon, a well-accepted published author, and established the position of a physician in childbirth, widening the gap between genders in women’s medicine in the 16th and 17th century.

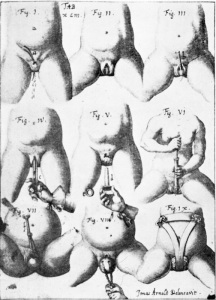

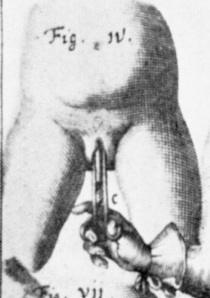

These images are the first illustration of excision for clitoral hypertrophy provided by the German surgeon Johann Schultes (aka Scultetus 1595-1645) in Armamentarium Chirurgicum published posthumously in 1655. While it’s not Guillemeau’s work, it gives a good idea on what such procedures looked like and were done during this time period. Additional info on them can be found at http://www.iscgmedia.com/1/category/clitoroplasty/1.html.

Pingback: Masculinization of Women’s Medicine in Early Modern Europe | Women in European History